As I was thinking about this process, TO CONSTRUCT HISTORY, I discovered a metaphor that seemed to make sense.

Imagine an assignment where students are often asked to take a poster and answer the question, "Who are you?" by making a collage using words and images from magazines. The student pores through magazines, cutting, pasting and organizing until the collage is a masterpiece. Even when finished, the collage doesn't communicate everything that can possibly be share about the individual, but it's a wonderful start. For a twist, I'm going to change how the poster is shared with others. Instead of letting the student present his/her own poster, imagine the teacher asking everyone in the class to make sense of the collage with this assignment:

Your job is to look at the evidence that is on the poster and create a brief narrative about this person based on what you see on the collage. Your narrative should tell me who this person IS.

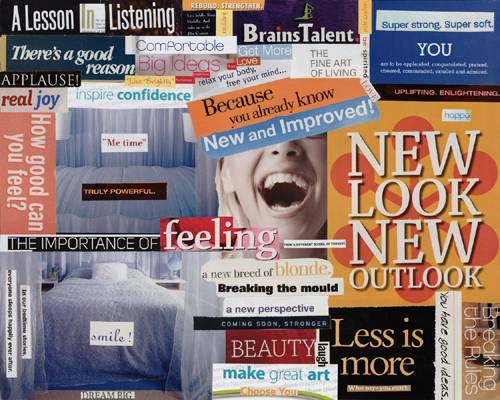

"Words to Live By", Anne B.'s Vision Board, Collage, 16 x 20 inches, January 2012. Anne's board is composed of 50 images; 48 of which are words or phrases!

I see this activity as a precise metaphor for what we want students to do when they construct history. Students should be taking all of the evidence that they have about a person, event, idea, or time period and make sense of it through considering how the different pieces and parts are connected. Connecting these pieces and parts involves high levels of critical thinking. Everyone will come up with different answers, which may be uncomfortable for a teacher who expects one common answer, but the different answers reveal each student's ability to construct history based on the evidence they have in front of them. If we don't let students construct history, then we leave them with snapshots of primary and secondary sources that have never been connected by the learner. To me, this is one of the most important steps in historical thinking.

What might this look like in a classroom? (As a note, I'm presenting ideas that are created for the sole intent of causing teachers of history AND historical thinking to consider how this might play out in a classroom. This is the product of my own reflection about quality instruction within history.)

First, I would want to use the timeline as a primary tool to keep track of the historical pieces of evidence. (Side Note: Timelines are, too often, tools that teachers use ineffectively. They end up being products instead of tools. We don't have a hammer, whisk, or spatula to look at - they are tools. Timelines must be created so they can be used as tools for the historian.) The timeline creates a holding place for a historian to keep track of historical evidence connected to people, events, and ideas over time. As students examine different sources, whether primary or secondary, they add pieces of evidence to the historical story we want young historians to tell.

For example, let's take a set of sources connected to the Stamp Act.

- Primary Source - Stamp Act Riots

- Primary Source - Letter from Archibald Hinshelwood 1765

- Primary Source - No Stamp Act teapot

- Primary Source - Ben Franklin's Testimony to Parliament 1766

- Primary Source - The Funeral of Miss Ame Stamp

- Primary Source - The Bostonians paying the excise-man, or tarring and feathering 1774

- Secondary Source - A description of tarring and feathering

- Secondary Source - Stamp Act synopsis from Gordon S. Wood

For most of the nation, student learn about early American history in 5th grade. As a class, the kids may have experienced different levels of support as they learned about the Stamp Act with each of these sources. Upon finishing this, I see a timeline with images or notes about each of these sources. To involve students in the critical historical thinking and the sense making process, their final task (in groups or on their own) might be:

Your job is to look at the evidence that is on your timeline and create a brief narrative describing the Stamp Act based on these sources.

Constructing history is something that is done by students, grounded in historical critical thinking. It involves the teacher giving up responsibility for telling the story and giving that responsibility over to the students. No matter what the final product happens to be, it will be connected to true educational goals - students engaged in critical thinking, sense making, and communicating their ideas based on evidence.